Authors:

(1) Youn Kil Jung, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, University of Science and Technology, and The KMTNet Collaboration;

(2) Cheongho Han, Department of Physics, Chungbuk National University and The KMTNet Collaboration;

(3) Andrzej Udalski, Warsaw University Observatory and The OGLE Collaboration;

(4) Andrew Gould, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, Department of Astronomy, Ohio State University, Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy and The KMTNet Collaboration;

(5) Jennifer C. Yee, Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and The KMTNet Collaboration;

(6) Michael D. Albrow, University of Canterbury, Department of Physics and Astronomy;

(7) Sun-Ju Chung, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute and University of Science and Technology;

(8) Kyu-Ha Hwang, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute;

(9) Yoon-Hyun Ryu, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute;

(10) In-Gu Shin, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute;

(11) Yossi Shvartzvald, Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science;

(12) Wei Zhu, Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Toronto;

(13) Weicheng Zang, Department of Astronomy, Tsinghua University;

(14) Sang-Mok Cha, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute and 2School of Space Research, Kyung Hee University;

(15) Dong-Jin Kim, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute;

(16) Hyoun-Woo Kim, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute;

(17) Seung-Lee Kim, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute and University of Science and Technology;

(18) Chung-Uk Lee, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute and University of Science and Technology;

(19) Dong-Joo Lee, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute;

(20) Yongseok Lee, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute and School of Space Research, Kyung Hee University;

(21) Byeong-Gon Park, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute and University of Science and Technology;

(22) Richard W. Pogge, Department of Astronomy, Ohio State University;

(23) Przemek Mroz, Warsaw University Observatory and Division of Physics, Mathematics, and Astronomy, California Institute of Technology;

(24) Michal K. Szymanski, Warsaw University Observatory;

(25) Jan Skowron, Warsaw University Observatory;

(26) Radek Poleski, Warsaw University Observatory and Department of Astronomy, Ohio State University;

(27) Igor Soszynski, Warsaw University Observatory;

(28) Pawel Pietrukowicz, Warsaw University Observatory;

(29) Szymon Kozlowski, Warsaw University Observatory;

(30) Krzystof Ulaczyk, Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Gibbet;

(31) Krzysztof A. Rybicki, Warsaw University Observatory;

(32) Patryk Iwanek, Warsaw University Observatory;

(33) Marcin Wrona, Warsaw University Observatory.

Table of Links

- Abstract and Intro

- Observation

- Light Curve Analysis

- Physical Parameters

- Microlensing Planets in the (log s, log q) plane

- Summary and Conclusions

- References

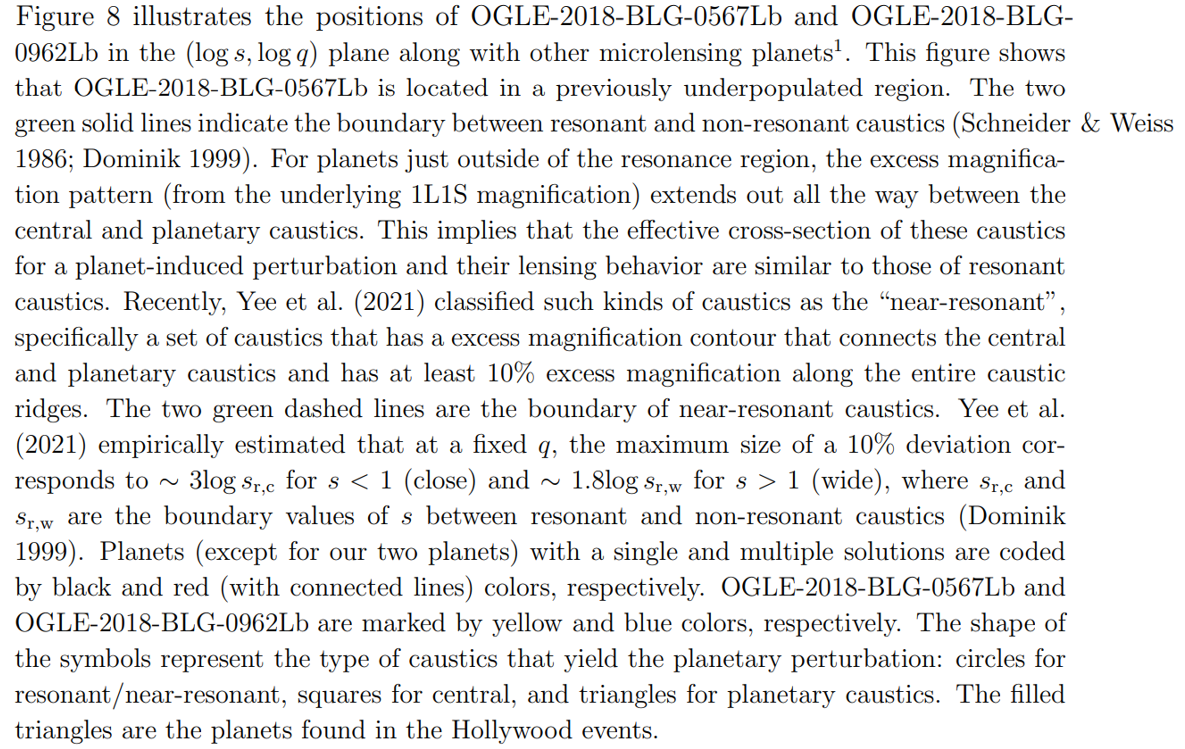

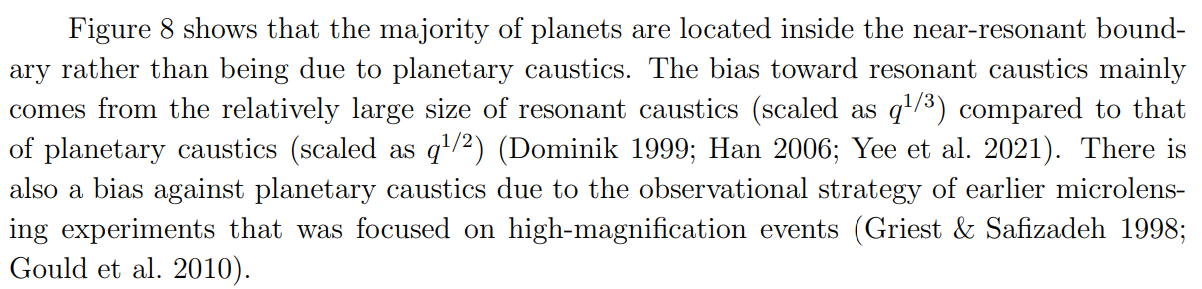

5. Microlensing Planets in the (log s, log q) plane

Our two survey-only microlensing planets are detected from the perturbations caused by the planetary caustics (see Figures 3 and 4). In particular, the planetary perturbation of OGLE-2018-BLG-0567 was generated by a “Hollywood” geometry (Gould 1997), in which the source size contributes strongly to, or dominates, the anomaly cross section relative to the size of the caustic. These detections prove the capability of the high-cadence surveys for detecting planets through the planetary-caustic channel.

Only 24 planets are placed outside the near-resonant boundary and 18 planets among them are detected from the perturbations produced by clearly isolated planetary caustics [2]. We find that most of these planetary-caustic planets (12 planets) are found in the Hollywood events and they are located in high-cadence observational fields of the lensing surveys. This proves the capability of the Hollywood strategy of following big stars to find planets (Gould 1997). The majority of the Hollywood planets are located in the region s > 1. This is mainly due to the difference in the size of planetary caustics. For s > 1, there is one four-sided planetary caustic. For s < 1, on the other hand, there are two triangular planetary caustics and each of which size is much smaller than that of s > 1. In addition, the planetary signals from these smaller planetary caustics tends to be more significantly diminished by the finite-source effects (Gould & Gaucherel 1997). As a result, the wide-planetary caustic has a larger effective cross section and therefore higher sensitivity for finding planets.

This paper is available on arxiv under CC0 1.0 DEED license.

[1] https://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu

[2] The corresponding planetary-caustic events are OGLE-2005-BLG-390 (Beaulieu et al. 2006), MOAbin-1 (Bennett et al. 2012), OGLE-2006-BLG-109 (Gaudi et al. 2008; Bennett et al. 2010), OGLE2008-BLG-092 (Poleski et al. 2014), MOA-2010-BLG-353 (Rattenbury et al. 2015), MOA-2011-BLG-028 (Skowron et al. 2016), MOA-2012-BLG-006 (Poleski et al. 2017), OGLE-2012-BLG-0838 (Poleski et al. 2020), OGLE-2013-BLG-0341 (Gould et al. 2014), MOA-2013-BLG-605 (Sumi et al. 2016), OGLE-2014- BLG-1722 (Suzuki et al. 2018), OGLE-2016-BLG-0263 (Han et al. 2017), OGLE-2016-BLG-1227 (Han et al. 2020), KMT-2016-BLG-1107 (Hwang et al. 2019), OGLE-2017-BLG-0173 (Hwang et al. 2018), OGLE-2017- BLG-0373 (Skowron et al. 2018), OGLE-2018-BLG-0596 (Jung et al. 2019), and OGLE-2018-BLG-0962 (this work).